The Revival of Tai Manuscript Studies in the 21st Century

Ven. Dr. Vijayabhipala[1]

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Introduction

Manuscript Studies in Tai living areas have been revising at the moment. To give evidence at the revival of Manuscript Studies, there are three sections connected with the learning Buddhism by the Tai/Shan. The first connects with Tai Manuscripts (Lik Loung) used at the traditional celebrations inside and outside of Shan State. Over ninety percent of Tai/Shan people believe in Buddhism in common with their neighbours of Southeast Asia such as Myanmar, China, Thailand, and Lao. Most Tai/ Shan people are Buddhist and learn Theravada Buddhism through listening to Likloung texts when the traditional celebration takes place. Tai/Shan Buddhists use Likloung texts to spread Buddhasāsana in an interesting way. These Likloung texts are traditionally read by Zares who are poetic readers. The second is connects with Likloung Conference which is successfully held in Tai areas. These conferences have shared knowledge of literature and culture withTai people. Tai is the original name but Shan is from syam pronounced by Burmese. Tai/Shan people have been living in Shan State, in the Northeast of Myanmar for many centuries. Outside of Shan State, there are some groups of Tai/Shan speaking living throughout other parts of Myanmar and neighbouring countries such as Tai Khamti in the Sagaing Division; Tai Assam in the northeast of India; Dai people in the Yunnan province of southern China; and Tai Yai in the northern of Thailand. The third connects with Tai Manuscript Department which provides courses at the Shan State Buddhist University. I strongly believe that the Lik Long tradition will continue to exist in many centuries.

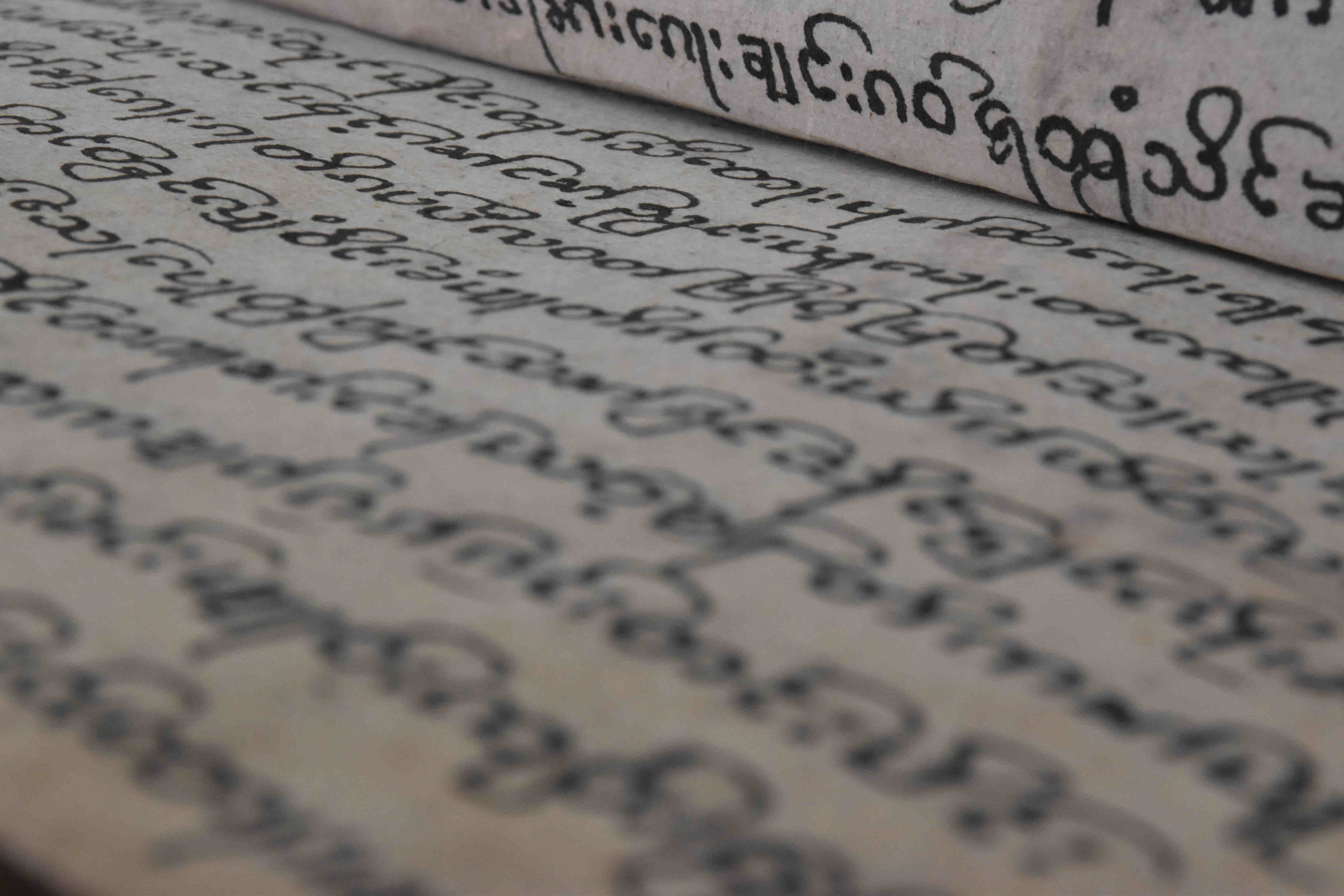

The Important Likloung Texts among Tai People

First of all, we will look at the learning Buddhism through listening to Poetic Literature. Poetic Literature known as Likloung have been more significant tradition and culture for Tai/Shan people. The Likloung texts have truthfully been composed by the Tai poetic scholars since the 16th century AC when we look back on the first scholar of Likloung, Sao Dhammadinna (1542-1641) and listen to them until the present. This section consists of significance features, characteristics and ritual tradition of listening to Likloung texts in Tai living areas. Most of Tai people are Theravada Buddhist and learn Buddhism through listening to Likloung texts when the traditional celebration is held. The Likloung texts would be written in poetic style and decorated with excellent prosody in Tai scripts. Kinds of Tai scripts in Likloung could be seen such as Tailoung, Taikhun, Taimao, Taikhamti, and Tai-Asam. Some Tai scripts are similar to each other but others are a little different between them. Although they are similar or different, the Likloung texts would be similarly composed in poetic style and written with Theravada Buddhist texts. In addition, Tai Buddhists use Likloung texts to deliver Buddhist teaching interestingly. Therefore, the reading and listing to Likloung texts are heart of Tai people.

Most of Likloung texts contain canonical Pāli text established at the 5th and 6th Burmese Buddhist councils. Some of Likloung, Tai manuscripts are based on Pāli and commentaries to the canon, e.g. Mahasatipatthan (1875) by Sao Amat Loung, and Kyam Naytang Nibban (Showing the Way to Nibbāna, 1930) by the Sao Warakhe, but some of them do not seem to be found in the Theravada Buddhist texts. Some may be connected with Tai Buddhism and folk literature. The types of popular folk literature which transmitted through Likloung include Bodhisatta and Jātaka stories. The terms which are used for Tai folk literatures would be apum, alaung, and watthu (also pronounce as wutthu). Apum refers to folk tales and alaung refers to the stories of the Boddhisatta to be a Buddha. Neither is necessarily derived from the early Buddhist texts. Some famous titles which belong to the alaung are: alaung nukao (the bodhisatta white mouse), alaungpya linneil (the clay bodhisatta), and alaung kai khao kham (the bodhisatta buffalo with gold horns). Watthu texts are stories based on Buddhist canonical literatures such as Jātaka and Dhammapada commentaries. Most of Tai people prefer listening to alaung and apum to other Likloung texts because they are really exciting and interesting.

Additional significance features of Likloung texts are that poetic authors usually transform from Pāli texts, the teaching of the Buddha, into Likloung texts in a way which is suitable for the Tai audience both literates and illiterates. The style of Likloung often gives humorous expression, a way of entertaining the audience and keeps the audience awake during long hours of recitation. In adition, Likloung texts have been composed in a way that the audience would be pleased while listening to them. Likloung texts themselves also apply to subjects regarding to social and religious activity, for instance, Ananda Daung Pan (the request of Venerable Ananda), which explains about Buddhasasana in the future and Kyattika Laowee Deing (the Big Dipper When Standing in the Middle of Sky), which talks about gratitude to each other. Therefore, Likloung texts make the audience more interested and amused when they are reading and listening to them during the recitation rituals.

And, Likloung texts have an excellent feature or rules which guide composers of Likloung texts to write them in prosody. There are several forms of rhyming systems, which the composers must use and the readers must also recognize anticipation to correctly recite Likloung. Some Likloungs have been called as Langka Aon and Langka Loung which means short rhyme and long rhyme. The term of langka is probably derived from the Pāli word, alaṅkāra literally meaning ‘decoration.’ Alaṅkāra has been found in the title of the Subodhālaṅkāra, which shows the rules for decorating the sentences or phrases, written by Sinhalese monk, Venerable Sangharakkhita in the 12th Century AD. Therefore, alaṅkā points to the decorating sentences in a poetic style. The composer or reciter of Likloung texts is usually called Zare, which refers to a poetic writer or reader. In accordance with the celebration for honouring Shan scholars (1982- present) in Panglong, the town where I grew up, ten numbers of well-known poetic writers were described.[2] But other lesser-known poetic writers, for instance, Sao Zekung of Wanzing, Sao Punnya of Wan Yok, and so on are still remaining.

Likloung texts are quite difficult to literately compose. They should be composed with the names of kio (strands) and namkawm (paragraph) in accordance with the techniques of poetic scholars. The strand is divided into two types, e.g. saungkio (two strands) and samkio (three strands). Of these two types of Likloung, there are also kawmpaut (short rhymed Likloung) and kawmyao (long rhymed Likloung) in the three strands and two strands, but sometime two strands are only used in kawmpaut (short rhymed Likloung). The both, long and short Likloung texts are literately composed with three systems of rhyming– 1) kiotang (the set up), 2) kiohop (the rhyme), and 3) kiolop (the end) in four paragraphs. The four paragraphs are as one group in the writing Likloung texts. The first paragraph is the end and setting up of rhyme, the second is the rhyme and leaving word (kwampaet). Leaving word here means the tones are not used for rhyming of the three strands. The third is the end and setting up of a new rhyme. The new rhyme for the setting up begins immediately in the third paragraph and the fourth paragraph becomes the rhyme and leaving word (kwampaet). The first paragraph of other group is the end and the setting up of rhyme and so on. Consequently, the composition will carry on and on by the round of three strands and four paragraphs from the beginning to the end of Likloung text. It is the three strands of rhyming which make this type of Likloung called langka sam kio (three strands of Likloung) and sea nam kwam (four paragraphs).

Tones are used as the keys for the writing of Likloung texts. There are four standard tones in Tai script: rising tone, middling tone, running tone, and falling tone. The four tones are surely used for the three strands of Likloung (langka samkio) while other rising tone and falling tone are used for the two strands of Likloung (langka saungkio). Usually, the first paragraph starts in rising tone and ends in running tone while the second paragraph starts in middling tone and ends in rising tone. The third paragraph starts in rising tone and ends in falling tone while the fourth paragraph starts in middling tone and ends in running tone. This is a symbol for the long and short three strands of Likloung texts (langka samkio). The example of short and three strands of Likloung texts written in poetic style and decorated with excellent prosody is as follows:

naile beinnang genzao larptam sawatthibay zeta uhyana kyanwark gornaw~ banlarnai.

satthe buktam kyangngurnkyangkham khangtam naisun kammurng luphalar~ ahtotdeyao.

liluheinglang saophang larkkurm kenlurng kyunthar maisarmzar~ tunkeyao.

khaobein alu lukman sumana sutatta dawnai tangzurl anahtabingti sanghteng bukte~ langkyangyao. (Suttan Pitakat, pages 2-3)

The above extracts are the first three strands rhyming system and four paragraphs as a group in Suttan Pitakat which is the most popular text in Tai Buddhism. The main rhyming and linking words are shown in bold and the underlining words which are called Langka Samkio the three strands of poem. The word lar in the first paragraph is called kio tang, ‘the set up’. It rhymes kio hop with lar in the second paragraph and zarin the third paragraph are called kio lop, the end. The last word of third paragraph keis kio tang, ‘the set up’ of a new rhyme. The word te in the fourth paragraph are called kio hop, ‘the rhyme’. The word htot at the end of second paragraph and kyang at the end of fourth paragraph are called kwam paet, leaving word. It will go like this i.e. the set-up, the rhyme, and the closing until the end of treatise. Therefore, this type of poem is called Langka Samkio (three strands of poem).

Likloung texts have been made of nature materials. They have been written on native hand-made mulberry paper known as Zesa in Tai language. Zesa have been produced in Jeng Lum village, Kun Heing Township, Loilem District, Shan State. There are various sizes that would be produced namely- small, medium, and large. The Tai term for the size of Likloung is angka for example, six angka for the small size, eight angka for medium size, and twelve angka for the large size. If a Likloung text is very long, it is usually divided into two volumes for example, in two manuscripts of the six angka size. The cost of a traditional Shan manuscript text is not cheap. A Zare of Panglong town told me that the price of a blank folded manuscript of six angka, the small size, is about thirteen thousands kyat, Burmese currency. Most works of Likloung texts are preserved in the form of traditional hand-writing with traditional ink, but a few Likloung texts have been printing press.

Likloung texts are especially composed to read out to the audience when Tai Buddhist people hold traditional celebrations and sleep overnight at the temple during rainy retreat. Likloung texts are carefully read in pleasant voice by a poetic reader to entertain the audience at the Buddhist celebrations while the audience sits quietly and listens to it in a grateful manner. A Buddhist celebration is sponsored by a donor. The donor should invite a Zare and discuss with him before the opening celebration. The celebration will be led by Zare from the beginning to the end. The time of listening to Likloung is usually performed from 8:30 to 12:00 in the morning and from 6:30 to 9:00 in the evening. When I asked him, Lung Zare Nyana, who is a poetic reader, told me that the Zare must be in a good manner and takes precepts at all time. Before reading, Zare must wash face and hands; invite the audience to take place; invite good spirit (sammā deva), but for funeral invite a person who has passed away; pay respect to triple Gems with the formula okāsa; take precepts; develop the powers of triple Gems; recite Paccayuddesa, the brief of Paṭṭhāna; and offer water, flowers, and candles to the Buddha. After all, the Zare starts reading Likloung text for two and three chapters or for two and three hours, but sometime the reading would depend on the celebration. After the reading and listening to the Likloung text, usually Zare and audience share merit with all beings, develop loving-kindness, and pay respect to the triple Gems with the formula okāsa for closing celebration. After closing the celebration, the donors make offerings such cash, food, and cloth and pay respect to Zare. But, the traditional celebrations are a little difference between the north and east of Shan State.

Now let us describe about the ritual texts, which are highly complicated rhyme and intended to be read out to the audience as a religious poetic work. The reading and listening to or the learning Dhamma from Likloung texts usually takes place when traditional and social cerebrations are held. During my research in 2013 and 2014, when I asked him, Lung Zare Nyana who lives in Panglong told us by his experience of reading Likloung texts that there are several occasions and lots of Likloung texts should be read. The occasions which he described are funerals, memorial services, blessing and moving to a house.

Firstly, at the funeral, people prefer listening to Likloung texts, for instance, Jatibhavasamvega (the fear of birth), Aniccasabhaw (The nature of impermanence), Sangkhengkopa (the nine corpses), Marananussati (reflection on death), and so on.

Secondly, at the memorial services people prefer listening to Likloung texts, for instance, Ratagunpe (Showing gratitude to parents), Lokapewut (the world of repaying), Dukkhadipanikyam (the course of explanation for suffering) and so on.

Thirdly, at the blessing and moving to a new house people prefer listening to Likloung texts, for instance, Mangalasaumseeppaet (Thirty-eight Maṅgala), Cintamani (Cintāmani gāthā), Aungpaetperng (Eight Victories), and so on.

Fourthly, at the blessing house, the hot and hostess prefer listening to Likloung texts, for instance, Ukzar Sudawgong Zeitpar (the seven possessions of holy person), Hurkham Saumseepzeit Lam (thirty-seven golden boards), and so on.

In the morning, Tai Buddhists have ambition to offer food to Sangha at home for blessing a house or family on the traditional and social cerebrations after Zare read Likloung texts. These performances of Likloung would be holding every week of the month.

Besides, there is a popular tradition of reading and listening to Thamvesantara text in the middle and east of Shan State every year in Learn Seav Eat called by Shan people, it usually takes place in October. Thamvesantara is derived from Vessantara Jātaka, the last fulfil perfection life. This Jātaka is the most popular in the Buddhist countries. Consequently, the Vessantara Jātaka was composed in the poetic Tai literature. While the ritual recitation is performed, they donate cups or bottles of water, candles, and cash according to stanzas (gāthā) in a chapter reading. Their belief is that if they perform the reading and listening to Thamvesantara text, as a result, there will be raining regularly and then rice, fruit, and vegetable will also grow well. The ritual listening to Likloung texts would be performed every month of the year.

However, the ritual tradition of reading and listening to or learning Dhamma from Likloung texts declined in somewhere of Tai living areas. For instance, Tai Khamti in the Sagaing Division, Tai Assam in the northeast of India, Dai people in the Yunnan province of southern China, and Tai Yai in the northern of Thailand do not have ritual tradition of reading and listening to Likloung texts when holding celebrations. Even, in Shan State of Myanmar there are no more Tai people who are really interested in listening to Likloung texts.

Activities of Likloung Conferences

While the active Likloung was falling into decline, a Likloung Conference arose in Shan State of Myanmar with intention to approve and promote the learning Dhamma in Likloung (manuscripts). The conference is successfully led by Venerable Prof. Dr. Khammai Dhammasami, the abbot of Oxford Buddhavihara in England and sponsored by the local Buddhist people. The Likloung Conference has been held for six times. Firstly, it was held in Aung Mye Pung Tha monastery, Yangon, in 2013; secondly, it was held in Holoi monastery, Laikha to mark Venerable Prof. Dr. Khammai Dhammasami’s 50th anniversary birthday, in 2014; thirdly, it was held in Kang Murng monastery, Lashao, the second big city of Shan State in 2015; fourthly, it was held in Jen Daw Yan monastery Mandalay, the second capital of Myanmar in 2016; fifthly, it was held in Pitaka and Mwedaw monastery, Panglong where I grew up, in 2017; and sixthly, it was held in Aung Khyan Sa monastery, Pyin Oo Lwin, in 2018. Presenters at these Likloung conference both men and women or locals and foreigners have interestingly participated. The committee would proceed to hold Likloung Conference in the future.

When looking at these conferences, we understand that the Likloung Conference encouraged Tai groups to learn Dhamma in Likloung texts inside and outside Shan State. For example, at the first conference which was held in Yangon, there were 43 presenters including me. I myself had an opportunity to give a presentation on the paper of “History of Anāgārikadhammapāla (1864-1933) who was a ‘Hero of Buddhasāsana’ in Sri Lanka during British invasion. At the second conference which was held in Laikha, there were 51 presenters; at the third conference which was held in Lashao, there were 50 presenters; and at the fourth conference which was held in Mandalay, there were 106 presenters. At those three conferences I did not have an opportunity to give a presentation but others I did. The fifth conference which was held in Panglong, there were 220 presenters including me. I myself had an opportunity to give a presentation on the paper of Phingtung Wang Panglong and Thamzao Laowee Durng, “Tradition of Panglong and History of Big Dipper,” and at the sixth conference which was held in Pyin Oo Lwin, there were 189 presenters including me. Again I had an opportunity to give a presentation on the paper of “A Study of Ten Future Buddhas from Many Buddhist and Non-Buddhist Texts.”[3] As a result of Likloung Conferences, the number of presenters has been grown up yearly and Tai people have understood the Dhamma in Likloung texts more than before.

Anyway, the Likloung conference was yearly held six years around the Union of Myanmar. It was successfully held in order to promote Likloung Studies; to know the value of Likloung; and to preserve culture, tradition, religion, and history of Tai in the region. For instance, at the third Likloung Conference held in Lashao, in 2015 there were foreign scholars, who are really interested in Tai literature and culture, participated in the conference and discussed about the Dhamma in Likloung texts with locals. Actually, this works makes Likloung conference become international standard.

In accordance with the Proverb of Venerable Prof. Dr. Khammai Dhammasami saying, “Treasure from Tai Great Texts (Likloung)” on the Paper Collection of the Likloung Conferences, there has treasure (knowledge) in Likloung texts. Treasure from the Tai great texts means knowledge but the treasure from the ground means gem. The digging treasure from the Tai Great Texts will not be end but the digging treasure from the ground will be end. In the Likloung texts, there are the teachings of the Buddha on the individual and social value which could not end to dig. In order to have value on the human being, however, we should dig treasure in the ground and adorn the body to be beautiful among the people. Similarly, we should take the knowledge from Likloung texts and adorn the mind to be beautiful in round birth (saṃsāra). For the reason that, in the early time persons who could learn Likloung texts felt kindness and were too polite, self-efficient, ethical, and social harmony. The teaching from Likloung texts is value to Tai people. Therefore, SSBU decided to establish the Centre for Manuscript Studies to promote knowledge on Tai and their literature and culture in Tai regions.

It is considered that the treasures which were taken from the ground should be protected by theirs owner. In the same way, the treasures which exit in Likloung texts have been protected by poetic scholars for a long time. Nowadays, it is the time of Likloung texts to be protected by Tai people with the understanding of value. Being value of gem, they must take prize of Likloung texts. However, if Tai people do not take prize of them, it means that they are the human beings who do not know the value of gem. In Likloung texts, there are not only the Buddha’s teachings which spread to every part of the world but also there have Buddhist tradition, Tai history, romantic story, and politics even psychology. Therefore, the Likloung texts are excellent value to Tai ethnic group.

Department of Centre for Manuscript Studies

After Likloung has been on the stages, Shan State Buddhist University SSBU,[4] founded in 2014 by Oxford Sayadaw, Ven. Prof. Dr. K. Dhammasami (DPhil, Oxford), take a role to develop Likloung tradition. In the SSBU, there are trained teachers and local as well as foreign students studying innumerable subjects. In addition to these subjects, the SSBU provides Lik Long subject to Zareys who are the experts in reading and writing of Lik Loung texts. This subject depends on the effort of Ven. Prof. Dr. K. Dhammasami who is the abbot of Oxford Buddha Vihara in Oxford (2003) and graduated from Oxford University with DPhil Degree in 2004. One day, Oxford Sayadaw has seen some students, who grow old and did not have opportunity to attend University when they were young, studied Oxford University to get a degree. Having seen the Oxford University gives opportunity to those students, Oxford Sayadaw thought “I am absolutely delighted to see the principle of Oxford University. I am going to use this principle for social workers in our university.” After a few years based on his thought, Oxford Sayadaw happily created Department of Centre for Manuscript Studies (CMS) at SSBU in 2019. The CMS started to run the study programme in 2020 and accepted BA student from local in the same year. Its programme will provide Shan mediums for monks and Zares (the poetic readers) who are already expert on Likloung. The purpose of Centre for Manuscript Studies is to promote value of Buddhist manuscripts which descended from the early period. The CMS continues to accept BA candidates for the 2022-2023 Academic Year. SSBU will offers a B.A, and tries to offers other degrees such as AM, PhD in Likloung Studies which emphasize critical study and research on the living tradition of Likloung texts.

The CMS provides programmes of Manuscript Studies (Likloung Studies) perfectly well. The programmes of Manuscript Studies are prescribed into numerous subjects such an Introduction to Tipitaka; Sutta Studies; Abhidhamma in Daily Life; Jataka Story; Learning Characteristics of Composition Lik Loung; Study Dhamma in Likloung; Meditation Practice in Likloung; Learning Languages, History of Theravada Buddhism, History of Tai/Shan Buddhism and Ayuveda. A teaching course will be built up 20 hours for each subject. The objective of these programmes, as prescribed into the Introduction to Tipitaka and Sutta Studies, the CMS intends to give Tipiṭaka knowledge to students; as prescribed into the Likloung Study, it intends to provide the Dhamma knowledge in Likloung; as prescribed into Language Studies, it intends to provide language knowledge such as Pāli, and English; as prescribed into the Buddhist History, it intends to provide historical knowledge in Buddhism; as prescribed into the Buddhist Meditation, it intends to be able to practise meditation and teach the people; as prescribed into Tai Buddhist History, it intends to have knowledge of history and as prescribed into Ayuveda, the traditional medicine, it intends to provide medical knowledge in Tai tradition. The programmes of Manuscript Studies in Tai medium are similar to the Buddhist Studies around the world.

Out of these subjects the students are also given homework to complete BA degree. Most students who attend at SSBU for BA Degree in Likloung have been working for social and religious activities are given official permission. All students are required to analyse one of Likloung texts which is an old and useful in Buddhasāsana for the second semester in Academic first year. If his work is successful at the presentation, the student gets 20 credits. Then, all student are required to compose one Likloung text about 100 pages for the second semester in Academic second year. If his work is successful at the presentation, the student gets 20 credits. This homework will contribute to the students to be highly skilled in composing Likloung texts.

Moreover, the CMS undertakes a project of Likloung catalogue and digitization. In 2019 there was a workshop of catalogue and digitization at SSBU led by Venerable Prof. Dhammasami and Dr. Devid Wharton, the cataloguing teacher from Lao. Invited Likloung experts around Shan State came to attend at the workshop. After the workshop, about 470 Tai Manuscripts at SSBU; about 130 Tai Manuscripts at Mwetaw monastery in Mong Kurng; about 135 Tai Manuscripts in Visuddhi monastery of Wan Yein have completely been catalogued and about 23000 Tai Manuscripts have been digitised by students from CMS. About 1000 will be catalogued at SSBU and thousands of Likloung are surely needed to catalogue around Tai areas. We believe that tf the project of CMS succeeds, Likloung, Tai manuscripts will take root and revive in Tai areas.

The Planning of Centre for Manuscript Studies

Reading and listening to Likloung is a valuable tradition and culture of Shan people in Shan State and elsewhere among Tai communities. The tradition and culture of Likloung will be preserved by the Centre for Manuscript Studies (CMS) at Shan State Buddhist University (SSBU). The tradition of composition Likloung texts or even, the reading and listening to Likloung texts have gradually declined in some parts of Shan State or Tai/Shan regions. For that reason, the CMS will take this opportunity to revive the tradition of Likloung such as composing, reading, listening and researching in the 21st century. The CMS is now providing BA Degree Programme in Likloung Tai for who are expert in reading and composing. The CMS will make an attempt to develop Likloung and Buddhist Manuscripts and their tradition and culture according to the path and plan established by SSBU’s the Executive Council.

The Motto of Centre for Manuscript Studies is as follows:

“Study, Preserve, and Propagate Likloung, the Great Texts”

“သင်ယူ၊ ထိန်းသိမ်း၊ ပြန့်ပွါး လိက်လုင် ကျမ်းကြီးများ”

“လဵပ်ႈႁဵၼ်း၊ ထိင်းသိမ်း၊ ပိုၼ်ၽေႈ လိၵ်ႈလူင်ႁဝ်း”

Based on the motto of CMS, Likloung is certainly needed to preserve. Therefore, the CMS should provide educational programme with the aim of composing a new Likloung Texts and understanding the Buddha’s teachings and Tai traditions as appeared in Likloung texts. The skill of composing, reading, and listening to Likloung texts are very helpful to spread the Buddha’s teachings among Tai people.

In order to sustain and further develop the Likloung tradition and culture, some functions of CMS will be fulfilled at SSBU and beyond. Firstly, the function of CMS is to fully provide programmes of teaching and learning for Diploma, BA, MA degree and short courses, and to collaborate with local and international experts and scholars of Likloung. Secondly, the function of CMS is to successfully do research on Likloung texts and Buddhist manuscripts. Thirdly the function of CMS is to transliterate from the old form into the new form of Likloung Texts. Fourthly, the function of CMS is to engage widely and opening with the practitioners and Tai communities in Myanmar and beyond. Fifthly, the function of CMS is to preserve the Buddhist Manuscripts and its culture, and develop the study of such manuscripts. These functions will support the development of SSBU’s vision and aim.

A five-year plan for the CMS will be briefly mentioned. First, the CMS will provide two terms of Likloung Courses to students in one year with SSBU’s calendar. And, the CMS itself will take educational matter, administrative matter, and finance matter with the policies of the Senate and implement the policies on the teaching and learning for Diploma, BA, MA degree at SSBU and at its branches in some parts of Shan State. Then, the CMS will develop Likloung texts such as composing, copying, and recording Likloung and preserve material culture of Likloung. Next, the CMS will provide training course for teachers who will be able to do research on the manuscript culture competently. Finally, the CMS will encourage students to go on a field trip to some places where Likloung or Buddhist manuscripts are kept. This plan would be to go by the advices of academic and administrative committee at SSBU.

As the action Points, in order to achieve the plans above, the CMS first will arrange own office, invite and accept staffs who are able to work in it. Second, the CMS will accept students yearly:

- In 2021-2, accept students who are already expert in Likloung during three years

- In 2023-24 accept Diploma and MA students

- In 2025 establishes branches in Shan State

Third, the CMS will try to receive funds from devotees in Myanmar and abroad. Fourth, the CMS will run the Likloung programme with lecturers and scholars in Myanmar and beyond. Last, the CMS will collaborate with individual and institution who share our aim and objective in preserving and propagating Likloung and Buddhist Manuscript and theirs cultures.

The traditions and cultures of Likloung and ancient Manuscripts would be preserved by the CMS throughout Tai regions of Myanmar and abroad accordance with CMS Motto “Study, Preserve, Propagate Likloung, the Great Texts. The aims and plans of CMS will be implemented by the Executive Council collaborating with other departments through the Senate’s advice. The projects of CMS should contribute to the tradition and culture of Liklong texts to be revived and flourished in Tai areas and beyond.

Conclusion

In conclusion, the traditional learning Buddhism through Likloung texts has been in the civil wars for a half of century and it declined even nearly to disappear or die. Nowadays, the learned monks and local Scholars, who are ethnic Tai/Shan national group still making an attempt to promote the traditional learning Buddhism through Likloung at the temples and the university or somewhere in Tai areas. Therefore, the activities of Likloung, Likloung Conference, and the Department of Centre for Manuscript Studies will bring tradition, literature, and culture of Tai people back to live. The reading and listening to Likloung or the learning Buddhism through Likloung which began in the 16th or perhaps 15th century AC is important culture of Tai national groups could be maintained or preserved.

References

Conference Proceedings: the 6th Likloung Conference. Myanmar: Tai Kamboza, Mandalay, 2018.

Paper Collection of the 4th Likloung Conference. Myanmar: Tai Kamboza, Mandalay, 2016.

Prof. Dr. Dhammasami, Ven. Shan State University: A Concept Paper. Myanmar: Yangon, 2014.

SCA-UK Newsletter, Vol.12. United Kingdom: SOAS, University of London, 2016.

Sao Koli. Suttan Pitakat. Tanggyi, Wungwan Press, 1994.

[1] Ven. Dr. Vijayābhipāla, the Operational Director, Department of Centre for Manuscript Studies, Shan State Buddhist University in Taunggyi, Shan State, the Union of Myanmar.

[2] Sao Dhammadinna (1542-1641); Sao Garng Hsur (1788-1882); Sao Koli (1823-1869); Sao Nang Kham Ku (1854-1918); Sao Armat Loung (1885-1905); Sao Naw Kham (1857-1896); Sao Warlakhe (1890-1948); Sao Pandita (1912-1990); Lung Tang Kay (1924-2017)); and Zare Ngurnyort (1933-2008).

[3] This is in the note of the 6th of Likloung Conference.

[4] It is a new or the first Buddhist University in Shan State of Myanmar known as the Shan State Buddhist University (SSBU). It was declared opening for function on the 6-7 of February 2016. The academic programme of Shan State Buddhist University stated with an MA and PhD in Buddhist Studies and English medium in 2018. Nowadays, at the Shan State Buddhist University, there are six Departments including Centre for Manuscript Studies (CMS).